Arabeta Channel

Truthliscious

Thursday 29 January 2009

BEN-AMI & MOUSSA

Tuesday 27 January 2009

Rumour has it

An E-mail warning you from going to the cinema theatres anymore as there is an ‘’absolute hardcore facts’’ that some sick minded stick needles and syringes, that have been smudged with HIV+ blood samples, into cinema seats. By searching the news and the internet around the globe trying hard to prove those allegations, I have found nothing.

Laughing my back side out after receiving an e-mail from MSN Hotmail regarding my account, as the content of this one was:

‘’ Dear Hotmail User,Because of the sudden rush of people signing up to Hotmail, it has come to our attention that we are vastly running out of resources. So, within a month's time, anyone who does not receive this email with the exact subject heading, will be deleted off our server. Please forward this email so that we know you are still using this account.WARNING WARNINGWe want to find out which users are actually using their Hotmail accounts. So if you are using your account, please pass this e-mail to every Hotmail user that you can and if you do not pass this letter to anyone we will delete your account.’’

The funny part is that millions of millions of users rushed immediately to forward this hoax to each other to every name in the contact list without even investigating or researching the whole thing. Which even without researching, their logic mind should tell them that MSN wouldn’t send such a thing as every e-mail provider competing in the market that they are the best and has the biggest storage space for your e-mail and bulk ones.

Another one was spreading all over the Sates and now our friends in Perfect_day@yahoogroups.com helped with the Arabic Egyptian version regarding Missing Children. You’ll get an e-mail contain innocent child pictures and asking you to spread the word to help find them. The whole thing started at first with stupid joke amongst friends and on MySpace® and Facebook®. If you ask what could be the reason behind this, it is very simple just for the laugh and it might sometimes create a news and chaos and fear among the society.

Today i have received and e-mail from perfect_day@yahoogroups.com regarding Tommy Hilfiger™ racist remarks against his costumers. First I have heard those rumours years ago but with slightly different version. As it was rumour in the US and Europe, the targeted audience was the African American, Asian, Hispanics, and Jews. Now after all those years the Arabs wants to have a share in this stupid hoax games they have added ‘Arabic Customers’ on the version. First of all i bet that nobody ever search those rumours or try to find out why a business man and successful designer would do such an idiotic act, as above all the logic and hoax, who is in the right mind in the Western world would attack the Jews and refuse to sell his products to them and so for the Black, and Hispanic even though deep inside him those are his beliefs. I have search this matter and I found that Tommy Hilfiger never ever been on Oprah show until this incident and was there just to put the record straight towards those stupid nonsense rumours. Before anybody of the Arab world start accusing me that i am defending the designer, I would like to say from my fashion perspective, i don’t really like his lines and i don’t really buy from his shops as I feel he is outdated and his cloth lines just not stylish enough. I have followed this article with Oprah Winfery clip from her show that it has been aired on May 2007 which way before those silly e-mail start spreading in the Arab world and asking people to boycott his products without even investigate the truth.

The bottom line of the article is not defending a specific character or a product as much as to be aware of what are receiving form tons of hoax and wrong information. Rumours could cause anger and fear, hatred and war, chaos and devastation. I hope that everyone would research more and read more about any subject he/she talking about before spreading it blind folded.

Thursday 22 January 2009

Where is Egypt Headed?

December 2008

Daniel C. Kurtzer, the S. Daniel Abraham Visiting Professor of Middle East Policy Studies at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, served as U.S. Ambassador to Egypt from 1997 to 2001 and U.S. Ambassador to Israel from 2001 to 2005. He is the author, with Scott Lasensky, of Negotiating Arab-Israeli Peace: American Leadership in the Middle East (USIP, 2008). This essay is based on his talk given November 20, 2008 as part of FPRI’s Robert A. Fox Lectures on the Middle East.

Over the past few decades, the processes that launched and strategies that unfolded in the early years of U.S.-Egyptian relations and the peace process have gone through a number of significant changes. In order to appreciate better what has and has not been accomplished over these years, it is important to understand what both countries sought to achieve. The U.S.-Egyptian relationship—despite serious strains, differences of view, and mini-crises—has been one of the most profound and productive bilateral interactions our country has enjoyed over these years.

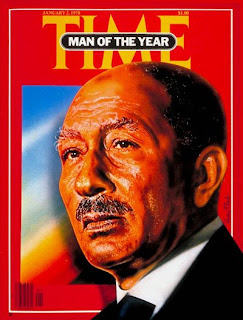

Anwar Sadat’s trip to Jerusalem in 1977 remains the unparalleled example of how leadership can, almost single-handedly, have a transformative effect on intractable conflict situations. To be sure, a decade of peacemaking efforts preceded Sadat’s diplomatic breakthrough. Gunnar Jarring was the UN peace envoy between 1967-70, tasked with implementing Security Council Resolution 242, the cornerstone of all peacemaking efforts in the Arab-Israeli conflict. Secretary of State William Rogers tried his hand at peacemaking in 1969-70 and left behind a peace plan that carries his name and a ceasefire plan that ended the Israeli-Egyptian war of attrition. The 1970 ceasefire was followed by the build-up to the 1973 Yom Kippur War, which heralded a period of significant U.S. involvement and the development of a new form of diplomacy. Henry Kissinger invented shuttle diplomacy, or step-by-step diplomacy, and secured disengagement agreements involving Israel, Egypt, and Syria. So, Sadat did not act in a political vacuum, but rather within a ten-year context of peacemaking. And yet Sadat is remembered, as he should be, as a leader who took a leap into the unknown that ended up transforming a political process into a diplomatic breakthrough.

Historical Overview

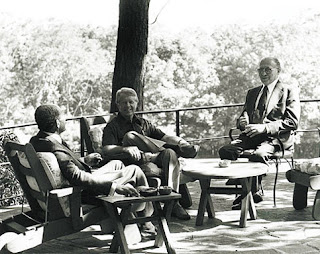

In 1977, the United States did not seem interested in doing what Sadat ultimately wanted to do, which was to develop a peaceful relationship with the State of Israel. The U.S. started that year trying to reconvene the Geneva Peace Conference. Historians still debate whether one of the motivations that drove Sadat to Jerusalem was his antipathy to the idea of going back to this conference format, in which Egypt’s national interests would likely be subsumed under the lowest common denominator decision-making of Arab politics. So Sadat went off on his own, in contrast or in reaction to what the U.S. had tried to do. But the U.S. was agile enough to understand that this breakthrough needed help in order to become a reality, and U.S. diplomats from the president on down soon caught up with Sadat’s breathtaking gambit. The remainder of 1977-79 became a swirl of diplomacy to consummate the breakthrough Sadat had launched in Jerusalem, culminating in the Camp David Summit and the peace treaty in 1979 under the sponsorship of the U.S. and with the U.S. as a witness. But success was never assured, either in the negotiations or in the implementation of the treaty.

It was an even heavier price for Egyptians, who recalled the period from 1952-79 when Egypt was the unparalleled leader in the Arab world. Under Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt had carried the banner of leadership in not just the Arab world but also the larger Muslim world, leadership based on its weight within inter-Arab circles and also on its leadership on the Palestine issue, anti-imperialism, in trying to develop what it called Arab socialism, and in branding itself as the leading party of secular pan-Arab nationalism. It even had pretenses to carry that banner of leadership in the non-aligned movement and in Africa.

When Sadat rose to power in 1970, and as a backdrop to what was to happen in momentous terms later in that decade, almost immediately he began to challenge every pillar of Nasser’s policies. In July 1972, after consolidating his own power in the face of a counter-coup launched by Nasserites who didn’t think Sadat deserved to be a leader, he ordered Soviet military advisors to leave Egypt, signaling a desire to rebalance Egypt’s relations with the U.S. At the same time, Sadat dispatched his national security advisor, Hafez Ismail, for two sets of secret talks with Henry Kissinger on ways to break the deadlock between Egypt and Israel in the Arab-Israeli peace process.

Sadat began dismantling the system of Arab socialism Nasser had tried to introduce, which had not only failed miserably but which had destroyed the Egyptian economy, substituting in its place what Sadat called the infitah or economic opening. The idea was that instead of socialism, there would be an opening for the private sector, for a capitalist economy to resume the role it had played in Egypt before the revolution.

Three Phases

When we look at the U.S.-Egyptian relationship, we can divide it into three periods, each with its own distinct characteristics.

The first period, from the late 1970s until the early 1990s, was marked by three strategic objectives. The first was to secure the peace treaty between Egypt and Israel. In the years 1979-82, the U.S. understood that the treaty’s strategic significance would be meaningless if it didn’t last as a monument for other countries in the region to emulate. Between the time the treaty was signed and when it was fully implemented, the U.S. devoted considerable diplomatic time and resources to ensure that the treaty was implemented fairly and honorably. It participated fully in the intense Israeli-Egyptian negotiations on bilateral normalization that were called for in the Camp David Accords. Israel and Egypt signed some 48 bilateral agreements during that period, and the U.S. encouraged the two parties to flesh out the relationship they had developed as a result of the treaty.

The United States also dramatically expanded its military and economic assistance to both Israel and Egypt in that period and helped create the multinational force of observers that has been in place ever since. It meticulously tracked the progress of the two sides in fulfilling their treaty obligations. One example tells a large story. At the end of the treaty implementation period in March 1982, Israel and Egypt agreed on the demarcation of the international border except in the area of Taba, an area of one square kilometer in the southeastern corner of Sinai. Israel had built a luxury hotel there during its period of occupation, believing that Taba was part of Israel and would remain so in a peace settlement; Egypt maintained that Taba was part of Egypt. Coming after a period of more than 20 years of armed conflict between two enemies, a border dispute now threatened the basic cornerstones of the treaty. Most territorial disputes at some point or another end in violence. And yet these two parties were able to resolve the matter through the dispute resolution mechanisms built into the treaty. The U.S. played an instrumental role in encouraging the two sides to fulfill the treaty’s arbitration obligations, and while it took seven years, the dispute was resolved peacefully.

Another U.S. strategic imperative during this period was to ensure that Egypt’s economy could emerge from what looked like imminent bankruptcy, stand on its own feet, and ultimately produce a peace dividend. This was no easy task, for Egypt’s economy was experiencing great stress in the late 1970s. The U.S. and Egypt decided first to tackle Egypt’s largest challenge, its infrastructure. Electricity, telecommunications, water, wastewater, and housing simply did not work. There were long blackouts almost every day, not only in the countryside but also in Cairo and Alexandria. It was nearly impossible to make international phone calls and a challenge even to call from one end of Cairo to the other. There was insufficient housing to accommodate the growing population and the mass migration of people into cities. The housing stock that did exist was being physically undermined by the wastewater and water that was seeping into the foundations, which led to building collapses all over Cairo. Over the next fifteen years the U.S. and Egypt agreed that U.S. aid would be devoted to improving this infrastructure. The results were in some cases astounding. Egypt not only built up its electrical power generating capacity, but also soon became a net exporter of electricity to Jordan, via a pipeline under the Gulf of Aqaba that’s part of the Mediterranean power grid.

Major water and wastewater projects were also undertaken throughout the country so that Egyptians could be assured of drinking water and that wastewater was being handled properly.

The second phase of the joint Egyptian-U.S. economic strategy started in the early 1990s, when Egypt committed to major structural reforms of its economy. The idea was that by liberalizing its economy, it would open up opportunities for job-creating enterprises. Egypt turned to the International Monetary Fund for help developing a macroeconomic structural reform program. Before going out as ambassador to Egypt in 1997, in meeting with IMF officials in Washington, I was pleasantly surprised to see their surprise in characterizing the Egyptian structural reform program as the most successful ever undertaken by the IMF. They had laid out a number of fairly onerous requirements for Egypt, and Egypt passed each of those tests, reforming many aspects of its economic policies in order to promote foreign direct investment and to create opportunities for the private sector. The results of the program were impressive. For example, by the late 1990s about 70 percent of Egyptian economic output was being generated by the private sector.

We are now in the midst of the third phase of this long-term U.S.-Egyptian strategy to assure Egypt’s economic growth and well-being, and the jury is out on whether this phase is succeeding. The question today is not one of infrastructure, nor is it still a matter of simply reforming economic policies. The hard work of creating opportunities and jobs and improving education and access to public services are the challenges Egypt faces today. Egypt will require more years to turn the corner and develop an economy that produces quality jobs in an environment of strong regulatory oversight but minimal governmental control.

The third element of U.S. strategy after Camp David was to transform the U.S.-Egypt strategic relationship and therefore the relationship between Egypt and the West. This involved in large part substituting American weaponry and U.S. military doctrine for Soviet weapons and doctrine. The thinking behind this goal was straightforward: for Egypt to be able to withstand the pressures of its isolation within the Arab world and to build strategic ties with the U.S. that would not be unidirectional—i.e., to build strategic ties in which both partners would contribute something to the relationship — Egypt needed enough military power to be a player in the region, but not enough to threaten Israel. Over the next thirty years, U.S. security assistance programs helped Egypt achieve these goals. The Egyptian military is a credible, well-equipped force, fully interoperable with U.S. forces.

Meanwhile, Egypt has maintained its military and security commitments under the peace treaty, both in letter and spirit, and there has been no serious violation of the military annex of the treaty. In the 1991 Gulf War, when the U.S. assembled an international coalition of allies to repel Iraq’s aggression against Kuwait, it called upon Egypt to contribute forces, and Egypt sent two fighting divisions to the front that fought alongside U.S. forces. They were fully interoperable with ours, they acquitted themselves well, they were able to maintain and use the weaponry, and they understood the nature of a complex modern military engagement. Equally and perhaps even more important, Egypt offered then, as it continues to do now, the facilities, rights of over-flight, and Suez Canal transits that are of crucial importance to U.S. forces deploying to or returning from the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean. Even when the two countries disagree with each other on policy, as we do with respect to Iraq, there has never been a question of Egypt’s willingness to offer this military assistance to the U.S.

Looking Forward

This brief historical overview underscores the importance of the 30-year bilateral Egypt-U.S. relationship. It’s important not just for what has been achieved, but also what it stands for as we look ahead. Our two countries, notwithstanding widely-divergent political cultures and a history of political and policy differences, have managed to find common ground on three important objectives—peace, economic development, and strategic relations.

Two contentious issues remain on our agenda and need to be addressed. The first involves sometimes intense differences related to the issue of Palestine and the Arab-Israeli conflict. Egypt charges the U.S. with “double standard” behavior—that is, judging Palestinians and other Arabs more harshly than Israel. Egypt wants the U.S. to press Israel to stop settlement activity and to implement UN resolutions on the conflict. Egypt was particularly frustrated by the inaction of the Bush administration on the peace process during its first seven years, when the U.S. backed away almost entirely from diplomatic engagement.

For its part, the United States has expressed concern about the nature of the “cold peace” between Egypt and Israel. Even if the security provisions of the treaty have been observed meticulously, almost none of the other treaty provisions relating to normal relations between the two sides has been carried out. There have been ambassadors, but almost no tourism, business relations, or culture ties between Egypt into Israel. The U.S. wants to see a more proactive and fair role by Egypt in supporting peace efforts, with Egypt not only acting as an advocate for Palestinian positions but helping the U.S. act as an honest broker and third-party mediator.

The second area of recurrent tension between the U.S. and Egypt relates to Egypt’s slow progress toward political liberalization and democratization. During the Bush administration, this issue heated up to a boiling point, as the administration defined “transformational change”—its phrase denoting rapid movement toward democracy—as a high priority U.S. foreign policy objective.

For Egypt’s leaders since the revolution, two imperatives have trumped all other political considerations. The first is insistence on political independence. Egypt is a proud country with a very long history. It will not enter into a formal alliance with anyone, West or East, and it will not turn over any part of its territory to foreign control. It is extraordinarily jealous of its sovereignty prerogatives, as are many countries that emerged from colonial rule. In this respect, U.S. pressure to democratize—while seen by Washington as an extension of the political liberalism that has guided our republic—is seen by Egypt as a foreign dictate and as interference in its domestic affairs.

A second constant in Egypt’s behavior since 1952 is a strong preference for stability over change. Egypt has always been essentially a military-agrarian society, traditionally governed by a highly centralized political system whose main purpose in history until very recently has been to control the regulation and distribution of water in the Nile Valley Basin. After the 1952 revolution, the strong penchant for domestic stability remained a constant, even when Egypt’s foreign policy was dynamic and revolutionary. Egypt’s three rulers since the revolution—Nasser, Sadat and Hosni Mubarak—have seen their role largely as maintaining stability and ensuring public order.

In this context, what the U.S. touts as the genius of our democracy and political culture—openness to change, ability to deal with offsetting centers of power, the distribution of governing power among three branches of government and at three levels of government, federal, state and local—these attributes are seen by Egyptian leaders as potentially undermining stability and upsetting the social order.

In many respects, the U.S.-Egypt dialogue on democratization is really a “duologue” of two independent monologues, stemming from two very different political cultures, in which neither side is clearly listening to the other. This is not an academic issue for either. President Mubarak is now 80 years old, so Egypt will face a presidential succession in the period ahead. That succession is likely to be stable, no matter who emerges as president. But the process of choosing the president and the openness of the system to new entrants and to really fair balloting and domestic political change are issues that are not yet settled. Michele Dunne of the Carnegie Endowment posed these questions in an article recently against the backdrop of regime efforts to intimidate opposition parties and to engineer the electoral system so as to guarantee the result preferred by the regime.1 The answers to these questions are as yet unknown, but will tell us a great deal about Egypt’s readiness to confront change.

Two critical questions thus emerge from this overview of U.S.-Egyptian relations. First, what are the long-term prospects for the bilateral relationship? Can our two countries sustain a set of basic understandings that will enable us to continue to build on this thirty-year strategic relationship? Second, will the issues that plague our bilateral ties—the peace process and the debate over democratization—be manageable? Can we find a way to differ without affecting the core of our relations, or will differences ultimately erode the foundations on which our relationship exists?

These questions are inextricably bound together. One of the most persistent aspects of our foreign policy and political culture has been the notion that democracy is an idea that other countries ought to embrace. Walter Russell Mead of the Council on Foreign Relations has described four strains of thinking in U.S. policy that reappear almost no matter who sits in the White House—what he calls the Hamiltonians, who favor an alliance between national government and big business; the Wilsonians, who look to America’s moral obligation and interest to spread American values and the rule of law throughout the world; the Jeffersonians, who seek to safeguard democracy at home and avoid unsavory allies and policies that increase the risk of war; and the Jacksonians, who emphasize our physical security and economic well-being, and while not seeking a fight, will not shy from one and will go all out to win, if provoked.2 All of our presidents have a little bit of all of these attributes in them. Our friends, as well as our adversaries, need to study this and understand the motivations that drive American leaders.

But by the same token, it behooves us to try to understand the political history and social culture that motivate the policies of other countries. Egypt is and will remain a land of contrasts, where rich and poor, urban elites and rural fellahin, Westernized business executives and Islamic fundamentalists, “Egypt-firsters” and pan-Arab nationalists will co-exist in a mosaic held together by a common past and a strong central government.

So what is to be done? First, we must recognize the value to both of us of the intimate bilateral relationship we have constructed over thirty years—that is, to avoid as much as possible escalating problems and differences into crises.

Second, both sides need to improve their ability to listen to each other. In our dialogue with Egypt, we need to listen to each other much more carefully.

Third, we have a mutual interest in working together, constructively, toward an Arab-Israeli peace settlement. Better use can be made of more positive Egyptian-Israeli relations as a demonstration effect for a comprehensive peace settlement.

Fourth, it would be wise for Egyptians to undertake their own internal assessment of the value of political liberalization, not one choreographed or coming under pressure from the outside. They need to shut out the noise from the outside and to look at themselves in a mirror. Egypt is in the midst of an interesting and challenging period in its modern political history, when there is uncertainty over succession, a serious threat internally from the Muslim Brothers and like-minded friends, and where nascent movements for political reform such as the Kifaya (Enough) movement or the Ghad (Future) party are seeking legitimacy. If Egyptians prefer not to listen to outside advice, then let the debate about reform flourish within Egyptian society.

في زيارة شمعون بيريس رئيس الكيان الصهيوني لدولة قطر

ليس قناة الجزيرة فقط ولكن أيضا حكومة قطر وأميرها أكدوا مرارا أن كل أفراد الشعب والمسئولين والذين عقدوا معهم صفقات تجارة وعلاقات متميزة .. كل هؤلاء سلموا على المسئولين الإسرائيليين بدون حرارة .. وقد أكدوا كثيرا على بدون هذه حتى لا يشطح خيال الحاقدين على الدول العربية المجاهدة فيتخيل أنهم سلموا عليهم بحرارة لا سمح الله.ـ

وما تعرفه المخابرات المصرية أكثر وأفدح ولكنهم لا يريدون أن يفعلوا مثلما فعلت المخابرات السورية والعراقية حين هددت دول الخليج بكشف ما لديهم إذا لم ينضموا إليهما فى جبهة الصمود والتصدى ومقاطعة مصر، وكانت الإمارات وعمان هما الدولتان الوحيدتان اللتان لم

هذا وقد أكدت قناة الجزيرة أن مفاوضات سوريا مع إسرائيل لن تكون بحرارة أيضا، وذلك لطمأنة الشعوب أن الجهاد مستمر وأن العمالة فقط فى مصر وأن تحرير بقية الأراضى المحتلة سيتحقق على أيديهم إن شاء الله ، على شرط وحيد فقط، هو أن تحصل سوريا فى الصفقة على قطعة من لبنان كما هو حلم العلويين منذ مئات السنين.ـملحوظة: الصور مرفقة فى ملف واحد.ـ

بقلم المهندس: محمود أنور

Saturday 17 January 2009

Hamas is a Creation of Mossad Israeli intelligence

Let us not forget that it was Israel, which in fact created Hamas. According to Zeev Sternell, historian at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, "Israel thought that it was a smart ploy to push the Islamists against the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO)".

Ahmed Yassin, the spiritual leader of the Islamist movement in Palestine, returning from Cairo in the seventies, established an Islamic charity association. Prime Minister Golda Meir, saw this as a an opportunity to counterbalance the rise of Arafat’s Fatah movement. .According to the Israeli weekly Koteret Rashit (October 1987), "The Islamic associations as well as the university had been supported and encouraged by the Israeli military authority" in charge of the (civilian) administration of the West Bank and Gaza. "They [the Islamic associations and the university] were authorized to receive money payments from abroad."

The Islamists set up orphanages and health clinics, as well as a network of schools, workshops which created employment for women as well as system of financial aid to the poor. And in 1978, they created an "Islamic University" in Gaza. "The military authority was convinced that these activities would weaken both the PLO and the leftist organizations in Gaza." At the end of 1992, there were six hundred mosques in Gaza. Thanks to Israel’s intelligence agency Mossad (Israel’s Institute for Intelligence and Special Tasks) , the Islamists were allowed to reinforce their presence in the occupied territories. Meanwhile, the members of Fatah (Movement for the National Liberation of Palestine) and the Palestinian Left were subjected to the most brutal form of repression.

Ahmed Yassin was in prison when, the Oslo accords (Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government) were signed in September 1993. The Hamas had rejected Oslo outright. But at that time, 70% of Palestinians had condemned the attacks on Israeli civilians. Yassin did everything in his power to undermine the Oslo accords. Even prior to Prime Minister Rabin’s death, he had the support of the Israeli government. The latter was very reluctant to implement the peace agreement.

The Hamas then launched a carefully timed campaign of attacks against civilians, one day before the meeting between Palestinian and Israeli negotiators, regarding the formal recognition of Israel by the National Palestinian Council. These events were largely instrumental in the formation of a Right wing Israeli government following the May 1996 elections.

Quite unexpectedly, Prime Minister Netanyahu ordered Sheik Ahmed Yassin to be released from prison ("on humanitarian grounds") where he was serving a life sentence. Meanwhile, Netanyahu, together with President Bill Clinton, was putting pressure on Arafat to control the Hamas. In fact, Netanyahu knew that he could rely, once more, on the Islamists to sabotage the Oslo accords. Worse still: after having expelled Yassin to Jordan, Prime Minister Netanyahu allowed him to return to Gaza, where he was welcomed triumphantly as a hero in October 1997.

Arafat was helpless in the face of these events. Moreover, because he had supported Saddam Hussein during the1991 Gulf war, (while the Hamas had cautiously abstained from taking sides), the Gulf states decided to cut off their financing of the Palestinian Authority. Meanwhile, between February and April 1998, Sheik Ahmad Yassin was able to raise several hundred million dollars, from those same countries. The the budget of The Hamas was said to be greater than that of the Palestinian Authority. These new sources of funding enabled the Islamists to effectively pursue their various charitable activities. It is estimated that one Palestinian out of three is the recipient of financial aid from the Hamas. And in this regard, Israel has done nothing to curb the inflow of money into the occupied territories.

The Hamas had built its strength through its various acts of sabotage of the peace process, in a way which was compatible with the interests of the Israeli government. In turn, the latter sought in a number of ways, to prevent the application of the Oslo accords. In other words, Hamas was fulfilling the functions for which it was originally created: to prevent the creation of a Palestinian State. And in this regard, Hamas and Ariel Sharon, see eye to eye; they are exactly on the same wave length.

Sunday 4 January 2009

Stop this Madness

I have had enough watching and hearing people everywhere trying to discuss who is wrong and whose fault was to start these events. Last night 3/01/2009 the Fourth strongest Army in the world Entered Gaza as second phase of their aggression against the Palestinian People. Israeli war planes dropping leaflets advising the Innocent armless civilians to leave their houses and take shelter?!

As everybody knows that there is no shelters or bunkers for the civilians in Gaza to hide. The borders are closed, and Israel Shelling them from every directions. I am absolutely not a fan of Hamas or any political or religious groups from both sides, but i am so angry and frustrated from the situation inside Gaza right now. The Israeli Prime Minister Spokesmen spreading his venim among the media agencies, as when he has been asked why you targeting Mosques and Schools, he claims that these are the Military warehouses belong to Hamas.

Israel refused untill today the 9th day of this bloody aggression for any foreign media to enter Gaza to broadcast from inside. What are they afraid of? What are they trying to hide? Or maybe they are the one going to put rockets inside mosques and school while they inside in the middle of the night, and then asked the international media to go inside and prove to them that was the reason they have entered and murder the innoccent armless people.

Saturday 3 January 2009

Egypt isn't South Beirut

Again the Leader of Hezbollah wants to continue his absurd accusation and plans to drag our nations into conflict with each other. I have talked to you before about Hamas, Hezbollah, and Muslim Brotherhood who Literally driving our conflict with Israel into different direction and what only approved with their Political Interests and the sake of Iran who is funding all these groups. Gaza massacres should stop now and immediately, but that is not going to happened. Israel has no right to kill and bombard the innocent civilians, and she knows very well they will never finish Hamas that way as they have failed before with Hezbollah.

Just now watching the international News TV around the world, i am listening to aid workers and other journalists calling their Stations fear for their and Gaza people lives. Israeli Ground Forces now entering Gaza in the middle of the night, but all the Hamas Leaders just vanished and hide and left the entire population are left in dark without any help or directions what to do or where to go. Another example for this crazy events that taking place in Gaza.

Every time i watch those children dead and injured bodies footage on TV, and hear these Israel and Western Leaders’ obtuse comments, the blood just boiled and i wish if i can jump of the Tele and spit on those clowns. I am Angry and i am sure there millions around the world are more angry, but we need to stop this big stupid game that all these evil powers are playing.

Israel, Hamas, Hezbollah, Iran, Britain, US, and all the Arab Leaders are just similar and have one thing in common. They all war criminals and involve us and our innocent brothers and sisters into a very deep and dirty world game.